The expansion of green, social and sustainable or sustainability-linked formats into short term instruments has the potential to boost overall volumes and impact, and pioneers have already begun testing appetite in the commercial paper market. However, the sector’s intrinsic characteristics raise questions over how to best exploit its potential. In this special Sustainabonds report, sponsored by ABN AMRO, Neil Day explores experience to date and asks what could catalyse growth.

You can download a pdf version of this article here.

In its most ambitious rallying cry yet, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) in October 2022 launched a manifesto highlighting five steps it suggested could quickly help green bond issuance reach $5bn annually by 2025. First among these was “Label Green”.

“Green labelling of bonds is now well established,” it said. “We must green the capital market ecosystem by expanding this labelling to include all types of financial instruments, from equities to short term borrowing, sectors, entities, and everything that comes beneath that, including transition, resilience, nature-based solutions, and water.”

The reference to short term borrowing came in the wake of a June 2022 discussion paper the CBI published on certification of short term debt instruments. Noting that green bond standards and definitions have thus far focused on $120tn longer term debt markets, it highlighted the potential of $55tn of short term debt.

“The rapid growth of investor appetite for green bonds, including some initial short term paper, suggests that there is potential to develop this market as a deep and liquid source of green capital,” said the CBI, which had convened a steering group to examine the issue.

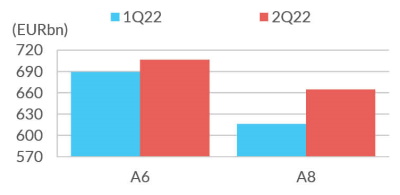

Research by Fitch Ratings also appears to support the growing investor appetite, in showing burgeoning money market fund assets under management (MMF AUM) being classified as Article 8 under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). It found that the proportion of total European MMF AUM classified as Article 8 at the end of the second quarter of 2022 was some €664bn, accounting for 47% of total European MMF AUM, up from 36% nine months earlier, while the share was as high as 74% for euro-denominated funds and 90% in France.

Fitch Ratings: 47% of European MMFs’ AUM are under Article 8 classification (2Q22)

Note: A9 funds not shown as they represent AUM of less than EUR2billion. Funds with no reported classification were excluded; Source: Fitch Ratings, Refinitiv Lipper

Such funds invest across a variety of debt, while CBI’s discussion paper ranged across short term instruments — from revolving credit facilities (RCFs) to export letters of credit. But arguably the most interesting for investors and most complementary for issuers already active in the green bond market, are commercial paper (CP) and, in the case of sovereigns, Treasury Bills (T-Bills).

As in the green bond market, the first such sovereign activity was greeted with much fanfare: on 18 October 2022, the Republic of Austria issued €1bn of four month T-Bills at a higher than average bid-to-cover ratio for the country, which had debuted in green bonds in May 2022. And as of 6 March this year, the sovereign is also offering green CP.

“The success of our first green Austrian Treasury Bill issuance shows the rising demand of ESG-compliant investments also in the money market,” said Markus Stix, managing director, markets, at the Austrian Treasury. “This is an important step for us to offer green instruments across the whole spectrum of the curve and strengthens the importance of the green pillar in our funding strategy.”

Short end a natural extension

When it comes to green, sustainable or ESG-labelled commercial paper, various early adopters echo this interest in a holistic approach to funding when explaining their motivation. When Dutch electricity and gas network operator Alliander, for example, established a €1.5bn green Euro CP (ECP) programme in July 2021, it did so within a green finance framework under which it already issued green bonds, and the company also had a sustainability-linked RCF in place.

“Greening the whole financial structure has been a driver,” says Alliander head of treasury Enno Dykmann (pictured below). “We started with green bonds in 2016 and then we had our corporate revolver, and an obvious potential third funding source was ECP. So it fits nicely into our CSR policy, of which green finance is a key part.

“We are a natural issuer on the green spectrum,” he adds, “and we felt it would be interesting for money market fund players to be able to invest directly in the grid components that allow people in the Netherlands to feed renewable energy back into the grid.”

“We are a natural issuer on the green spectrum,” he adds, “and we felt it would be interesting for money market fund players to be able to invest directly in the grid components that allow people in the Netherlands to feed renewable energy back into the grid.”

While the Dutch company has pursued a use-of-proceeds approach in line with its green bond issuance, Italian energy group Enel adopted an ESG-linked approach in line with its pioneering sustainability-linked bond (SLB) issuance when it updated its ECP programme in May 2020. The ECP programme reflects Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets and KPIs adopted by Enel at group level, an approach that now applies to some €97bn of debt and non-debt financial instruments, from SLBs to cross-currency swaps, and from factoring to FX transactions.

“This approach is very coherent with the group’s overall strategy,” says Giovanni Niero, head of capital markets at Enel. “We are putting our money where our mouth is by embedding our KPIs and our targets in every financial tool that we use.

“Investors can therefore clearly understand that the issuer is seriously committed to these sustainability targets.”

Enel SpA has a €8bn CP programme (via Enel Investment Holding BV), while Enel Finance America and Spanish subsidiary Endesa each have €5bn programmes, bringing the group’s aggregate SDG CP volume to up to €18bn. (See accompanying article for more on Enel’s strategy and ESG-linked CP.)

Like Enel, Germany’s Münchener Hypothekenbank has long been a pioneer in the ESG field and in August 2019 the bank supplemented its sustainable covered bond issuance with green commercial paper, issued under the same overall financing framework.

“The idea was born out of investor feedback arising from the lack of products for green money market funds,” says Claudia Bärdges-Koch, head of debt investor relations and client acquisition at MünchenerHyp.

Justin Eeles, partner, chief investment officer, Affirmative Investment Management (pictured below), backs this up, citing the attractions of green and ESG CP.

“Short term debt instruments are an important tool for managing duration or addressing specific portfolio needs,” he says. “The availability of high quality, short term impact debt instruments has so far been limited.

“Short term debt instruments are an important tool for managing duration or addressing specific portfolio needs,” he says. “The availability of high quality, short term impact debt instruments has so far been limited.

“They offer a better alternative than cash,” adds Eeles, “normally higher yield, and with impact. We have one short-dated enhanced cash US dollar fund with a natural appetite for this paper.”

Where there’s a will, there’s a way

However, a few years on from the first green and ESG CP, it remains, in the words of Bärdges-Koch, “a niche product”.

Among the reasons sometimes proffered for the lack of growth — especially when compared to segments like green and more recently social bonds — is a possible conceptual mismatch in financing longer term assets with shorter dated instruments, and accompanying practical challenges, such as reporting.

But proponents of green and ESG CP say that these should neither in principle nor in practice prove problematic. The CBI, for instance, considered whether a link between the tenor of an instrument and the financed assets should be established, and answered in the negative.

“The steering group concluded that short term instruments do have an important role to play in the green finance market and the maturity of the instrument does not have to match the maturity of the assets financed by this instrument, so long as the underlying assets are aligned with the Climate Bonds’ or EU taxonomy and criteria.”

While green and ESG CP issuers have seen little in the way of objections to bringing short term debt into their sustainable issuance, Austria tackled any mismatch concerns by committing to roll over its green T-Bills as long as it is active in green debt issuance — last year it had identified over €5bn of eligible assets, of which the majority was financed through its €4bn debut green bond in May 2022, and it expects volumes to grow, allowing for the expansion into green CP. The debt is all included in the same allocation and impact reports.

“Some issuers see maturity mismatches as a challenge, particularly given increased reporting commitments,” says Eeles at Affirmative Investment Management, “but the Austrian model shows this can be overcome.”

While Austria and others may have sufficient assets to commit to ongoing issuance, not everyone does.

“It depends on the nature of the issuer,” says Dick Ligthart, director, Sustainable Markets at ABN AMRO (pictured below). “We’ve mainly seen green and ESG CP from the utility sector, where companies need to make substantial capex investments on an annual basis, so for them, it’s relatively straightforward to link the CP tranche to these for the period outstanding.

“We’ve seen issuers like MünchenerHyp link it to a portfolio of green assets, but for other issuers, it could be more complex.”

“We’ve seen issuers like MünchenerHyp link it to a portfolio of green assets, but for other issuers, it could be more complex.”

Issuers may also prefer to use their prized green assets for bonds rather than CP, particularly those with limited capacity, which may be further restricted if issuers are targeting EU Taxonomy alignment.

“While there are issuers who have plenty of available assets, it’s a bit challenging for those who have a very limited pool of assets,” says Joop Hessels, head of Sustainable Markets at ABN AMRO, “because then they have to make a choice, are you going to use it for a bond, or are you going to use it for commercial paper? I guess they will use it where they get most bang for their buck, i.e. green bonds.

“Alternatively, they can use CP while they build up assets until the time when they have enough to do a bond takeout.”

Dykmann at Alliander says this was part of the rationale for the company introducing green CP as a complement to its green bond issuance. MünchenerHyp, meanwhile, uses its green CP to finance that part of mortgage loans that is not eligible as collateral for its ESG Pfandbrief issuance besides using these assets for issuing green senior bonds.

“Fortunately we did not have to go through the new product process, as it was only a product variant,” says Bärdges-Koch (pictured below) in Munich. “Treasury can easily set a flag for green while implementing the new CP.

“With a maximum tenor of 364 days, mismatches are not a big challenge compared to capital market bonds,” she adds. “Furthermore, it was not a big effort to extend the reporting around the product — the set-up was already existent.”

“With a maximum tenor of 364 days, mismatches are not a big challenge compared to capital market bonds,” she adds. “Furthermore, it was not a big effort to extend the reporting around the product — the set-up was already existent.”

Like its green bonds, MünchenerHyp’s green CP complies with the Green Bond Principles (GBP), and many market participants see these as a sufficient backbone for the short term product, without the need for any new specific use-of-proceeds standard.

Alliander’s green financing framework is aligned with the GBP and also the Green Loan Principles, and further targets alignment with relevant EU Taxonomy technical screening criteria — something affirmed by ISS ESG in its second party opinion.

Like others to have adopted green CP, the Dutch corporate issues off a separate programme to its regular commercial paper programme.

“We were advised that to make sure that everyone can see that this really is green ECP, you should have a different programme,” says Dykmann. “There are some costs associated with having a second programme, but these are relatively minor, and because we are in the early days of this market, we thought it would be very important that there be no doubt among investors as to whether this is green ECP or not, so we followed that advice.”

Bloomberg meanwhile offers the option for green or ESG CP to be tagged with a green leaf as a way to flag its nature to investors and other market participants.

Tackling CP idiosyncrasies

Like it or not, the “greenium” is an ever-present topic in the green bond market, with a sufficient body of evidence pointing to its existence in many circumstances. But when it comes to green and ESG CP, there is scant evidence of a similar phenomenon.

According to Bärdges-Koch, MünchenerHyp is able to price its green CP 2bp inside its regular commercial paper, but market participants suggest the Bavarian lender could be the exception that proves the rule.

“MünchenerHyp is not one of the biggest issuers and is one of those German names that enjoy the strong support of their local network,” says Giles Chapman, head of commercial paper at ABN AMRO, “and there may well be some investors who will pay a bit of premium because it is green.

“But from where I’m sitting, particularly talking to some of the larger money funds, we are not seeing that readiness to pay up for green CP yet.”

He cites the example of Bayerische Landesbank, which offers both green and regular CP at the same levels.

“When investors want to do, say, three months at X% in euros, if I say, do you want classic or green? they might as well have green,” says Chapman.

“But if I say, you can have classic at X% or green at X% minus 2bp, I’m pretty confident they’re going to go classic every time.”

Echoing the fundamental view of many green bond investors, Eeles at Affirmative Investment Management argues that green and regular CP should trade in line with each as they are the same credit.

“Any differences would come due to an assessment of the issuer as a credit,” he adds, “as growing amounts of sustainable securities issued could indicate the business being managed for a changing environment and a commitment to sustainability, especially relative to peers slower to incorporate all areas of sustainability into their business. Therefore, we would not accept a greenium.”

A further hindrance in greeniums emerging is the private sales process when compared with green bonds, suggests Hessels at ABN AMRO.

“If you would ask green bond investors if they would pay up a couple of basis points for a green bond, they would say no,” he says.

“But in the bookbuilding process for a public bond transaction, with a large oversubscribed book, there is price tension and hence they perhaps end up with a tighter transaction.”

The shorter term nature of CP also undermines a potential argument in favour of greeniums that could be used to support them in longer term green bonds, namely that regulatory and other changes will justify a greater differential between green and non-green bonds further down the line — something that is not going to materialise in the three months’ or so life of green CP.

In general — and akin to green, social and sustainability bond issuers — those who have taken up green and ESG CP highlight that greeniums are anyway not a priority.

“CP is an auction and there is room to improve transparency in this market,” says Fabio di Renzo, Enel’s head of treasury (pictured below). “We are in the market every day, so we can say what a fair price is, but if you say there is a discount when we issue, I can’t confirm it.

“At this stage, it is not important to have a change in pricing,” he adds, “it is important to have greater sensitivity in the behaviour of corporates and investors.”

“At this stage, it is not important to have a change in pricing,” he adds, “it is important to have greater sensitivity in the behaviour of corporates and investors.”

According to Francesca Borraccino, head of cash and solvency management at Enel, the Italian corporate has also not witnessed a notable difference in interest in its CP since it gained its SDG status.

“The main driver was our internal strategy,” she says. “We didn’t receive any push from investors, because even before the programme became ESG, the principal investors told us that they already put our CP in their sustainable portfolios.”

Critical mass for a virtuous circle

However, some have expressed disappointment at both the lack of greenium and what they see as a wider lack of engagement on the green issue in the CP market. One funding official says progress is not helped by the opaque nature of the market, as alluded to above.

“When we first issued our green commercial paper, we didn’t get a very enthusiastic response from our dealers,” he says. “My impression was they basically offered it to the parties they were always doing business with — it wasn’t really promoted that this was actually green paper being offered. But that’s the whole difficulty with the CP market, that from an issuer’s perspective, it’s not very transparent, and we don’t know from the dealers where the paper ends up, with a green investor or not.

“I didn’t expect a greenium comparable to green bonds immediately,” he adds, “but I would have expected that increased demand would have let to some pricing pressure. So, as a consequence, we have basically stopped issuing green paper.”

Greater engagement among dealers and especially investors is considered the key ingredient that could result in a wider menu of green and ESG CP.

One fundamental driver of demand has fortunately moved in favour of this: Bärdges-Koch at MünchenerHyp notes that the negative yield environment made the timing of its introduction of green CP somewhat counterproductive.

“Flows in CP were low, and the market preferred SSA issuers at that time,” she adds. “The rise in interest rates alone in the past has significantly increased interest in CP.

“And coming back to positive yields, we were able to start with the green CP.”

Besides macroeconomic developments outside the control of market participants, the sector faces something of a “chicken and egg” problem, in the words of Chapman at ABN AMRO.

“There’s relatively little supply, because there’s relatively little demand,” he says. “And I think a lot of the money market managers are understandably wary of marketing a fund as green in case they do get a flood of money coming in and then find there’s very little to buy on the other side, as they’d then be a bit stuck.

“But it would only take a couple of the big money market players to launch such funds to turn things around.”

This, says Chapman, would require not just a greater number of issuers, but greater representation from those with outstandings sufficient to satisfy the needs of the bigger European and US money market funds seeking blocks of €100m or more.

Regulatory developments are meanwhile likely to see an increase in Article 8 and also the stricter Article 9 funds.

“In general, investors are having to indicate to what extent they are aligned with the EU Taxonomy or ESG topics in general,” says Hessels (pictured below), “so it helps if a security has a label that can allow them to tick as many boxes as possible.

“And as was the case with green bonds, while there was initially a focus on dedicated green bond funds, it has become much more important for regular funds to also include ESG elements in their analysis.”

“And as was the case with green bonds, while there was initially a focus on dedicated green bond funds, it has become much more important for regular funds to also include ESG elements in their analysis.”

“That will also be the case for money market funds,” adds Ligthart. “Indeed, if we go out for a green bond roadshow, we sometimes get questions for issuers like, do you also offer green commercial paper?”

If the chicken and egg problem can be overcome, a virtuous circle could emerge, suggests Eeles at Affirmative Investment Management.

“Greater availability of this paper is likely to beget additional demand, as happened with the green bond market, and will likely lead to shorter term products being established, again boosting demand,” he says.

“Corporate treasurers are likely to have growing demand when paper exists, as it would allow them to green their assets and help signal that sustainability issues are being incorporated in all areas of their business, which could boost investor demand for their securities.”