Issuers lacking projects appropriate to use-of-proceeds green bonds but with clear sustainability targets and transition strategies are increasingly finding sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) a viable alternative for reflecting their ESG ambitions in the capital markets. In this special report, sponsored by ABN AMRO, Sustainabonds’ Neil Day explores the surge in issuance and finds out what issuers need to be doing to win over investors.

A pdf of this article and accompanying Gasunie case study can also be downloaded here.

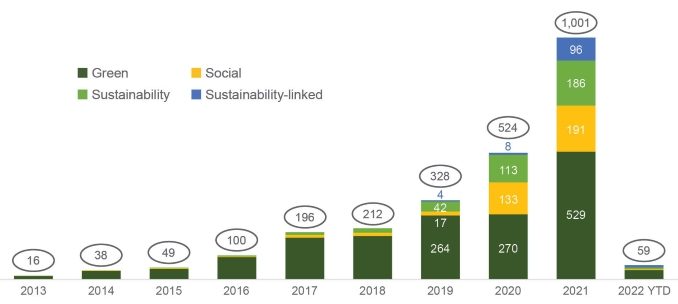

Although green bonds comprised half the market in use-of-proceeds and sustainability-linked instruments last year, 2021 was arguably the year of the sustainability-linked bond (SLB). From just around $4bn-equivalent of SLB issuance in 2019 and $8bn in 2020, the market boomed to some $96bn (€87bn).

“That’s very exciting and probably beyond anyone’s expectations for such a young instrument only launched in the back-end of 2019 by Enel,” says Dick Ligthart, director, sustainable markets, at ABN AMRO.

The Dutch bank is forecasting potential growth of around 150% for SLBs this year, which would take 2022 issuance to more than $200bn. Regardless of the issuance volume, the bank expects SLBs to leapfrog social and sustainability bonds in terms of market share.

SLBs take a growing share of the GSS bond market (US$ bn)

Source: ABN AMRO

Beyond the pioneering sustainability-linked bond issuance from Italian energy group Enel in autumn 2019, two initiatives are widely seen as catalysing the growth of the SLB market.

Firstly, the launch of the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (SLBP) by the executive committee of the Green Bond Principles (GBP) and Social Bond Principles (SBP) in June 2020. This laid down five core components of sustainability-linked bonds, including the selection of key performance indicators (KPIs), the calibration of sustainability performance targets (SPTs), and bond characteristics.

Secondly, the September 2020 announcement by the European Central Bank (ECB) that it would from 1 January 2021 accept bonds with coupons linked to sustainability (climate-related or environmental) performance targets as collateral, and potentially buy them under its Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).

“It’s very impressive how this new instrument has been taken up by issuers, particularly after the publication of the SLBP by ICMA,” says Ligthart. “What also really helped was the ECB’s very significant step of explicitly supporting this new type of sustainable bond.

“That strengthened many issuers in their belief that this would be a very credible alternative to regular green or social bond issuance, and opened up the market for companies that had maybe been sidelined in the traditional use-of-proceeds market because they lacked the appropriate level of green assets or investment programmes but were nevertheless working towards very tangible sustainable results.”

Investors give SLBs a fair hearing

The enthusiasm of issuers to find ways of getting involved in sustainability instruments is matched on the buyside. 65% of investors surveyed by ABN AMRO at the turn of the year expect to increase such assets by up to 20% in 2022 and 12% expect even greater growth.

While SLBs have ridden this green wave, their inherent characteristics have proven attractive to investors, according to Ligthart (pictured).

“Investors increasingly appreciate that companies are holding themselves accountable to their corporate ESG targets and are willing to accept a financial downside should they ultimately miss them — you’d better be committed to targets if you include them in an SLB.

“Investors increasingly appreciate that companies are holding themselves accountable to their corporate ESG targets and are willing to accept a financial downside should they ultimately miss them — you’d better be committed to targets if you include them in an SLB.

“That’s a powerful signal to send out as a company.”

Among investors gearing up for the boom in sustainability-linked bonds is AXA Investment Managers, which sees the product as having a bright future as well as the potential to offer clients long term, sustainable performance. Last month it published a framework it has developed for assessing the new product, noting the voluntary nature of IMCA-managed principles and guidelines.

“Like everyone else, we have been monitoring this nascent market and our portfolio managers have been buying some SLBs on an ad hoc basis,” says Théo Kotula, ESG analyst at AXA IM. “But in a similar vein to what we did for green, social and sustainability bonds, we decided to form a more stringent approach to this market and not take any SLB at face value, but undertake a deeper analysis of this new structure.”

Asset manager Actiam has also been engaged in the development of the market, even though Foppe-Jan van der Meij, senior portfolio manager at Actiam, says the firm still prefers use-of-proceeds bonds, seeing sustainability-linked bonds as complementary.

“We know that several sectors are not able to participate in the use-of-proceeds market,” he says, “and for these companies, SLBs are a really good addition. However, it is important that they explain why they are using that instrument and not use-of-proceeds, and also that the KPIs of their bond are a good translation of the sustainability targets of the company — if they have a good explanation, then we will stamp them as sustainable.

“We heard of one issuer saying that reporting for use-of-proceeds bonds is a bit challenging when discussing the rationale for sustainability-linked bond issuance,” he adds, “and if there is no good reason why they are turning to SLBs, then we would say, that’s not something for us at the moment.”

As examples of appropriate companies, van der Meij cites Nederlandse Gasunie (see case study) and H&M. The Swedish fashion retail group issued a €500m 8.5 year sustainability-linked bond in February 2021, with emissions reductions and an increase in its use of recycled materials as sustainability performance targets.

“For some issuers it’s just too difficult to source €500m of real green or transition projects for a use-of-proceeds bond,” he adds, “but an SLB can be really fitting.”

His Actiam colleague, responsible investment officer Tessa Eerenberg-van Kesteren, notes that the greater range of companies that can issue sustainability-linked bonds also offers diversification opportunities for investors.

“If you take the SLB of H&M,” she says, “this was a good way for Foppe to diversify from all the utility companies issuing green bonds.”

A viable transition option

A consensus is emerging that sustainability-linked bonds are well-suited to financing the transition, whether they are being issued by companies without appropriate assets for a use-of-proceeds bond, or ones with activities that cannot yet be clearly defined as appropriate for either a green bond or a transition bond. Although ICMA published a Climate Transition Finance Handbook in December 2020, transition bonds have not taken off.

“SLBs are a great way to track and evidence the transition that a company is making,” says Ligthart at ABN AMRO. “It also moves away from the discussion you have around transitional activities, which has been understood to imply that they are being labelled green or light green, and that potentially raises reputational risk — just look at the debate around the inclusion of gas and nuclear in the EU Taxonomy.

“The SLB format is a very viable alternative for companies in transition. Take cement producers, for example: we’ve seen a few tap the SLB market already, but had never seen them in the use-of-proceeds format — that shows the added value of the instrument.”

The cement industry contributes to about 7.3% of global industrial carbon emissions, according to ISS-ESG, which provided the second party opinion for LafargeHolcim when it was the first from the building materials sector to issue a sustainability-linked bond, a €850m April 2031 deal in November 2020. The Swiss-based company’s SPT is a reduction in net CO2 emissions (kilogrammes of CO2 per tonne of cementitious material produced) by 17.5% by year-end 2030.

AXA IM has been a proponent of transition bonds, but, echoing Ligthart, now sees SLBs as a complementary and potentially powerful tool for high-emitting issuers to finance their transition towards more sustainable business models.

“We have been working a lot on transition use-of-proceeds bonds,” says Kotula (pictured), “and, in our opinion, SLBs are in the same vein, meaning more transition than pure green or impact investments.”

“We have been working a lot on transition use-of-proceeds bonds,” says Kotula (pictured), “and, in our opinion, SLBs are in the same vein, meaning more transition than pure green or impact investments.”

So whereas use-of-proceeds bonds have been included in the firm’s green and impact investments, SLBs are likely to be included in its transition investments.

ABN AMRO’s survey also suggested that sustainability-linked bonds could prove a better means of tapping into investor demand for ESG investments than use-of-proceeds transition bonds, with 65% of accounts deeming SLBs relevant or highly relevant versus 53% for transition bonds.

In line with this, Italian gas infrastructure operator Snam also took up SLB issuance in January after having been one of the few corporates to issue transition bonds (under the moniker Climate Action Bond (CAB)). Whereas investments in biomethane and energy efficiency were among the use-of-proceeds of Snam’s CAB framework, the €1.5bn dual-tranche SLB issuance was more directly linked to its sustainability targets, with KPIs linked to reductions in natural gas emissions and Scope 1 and 2 emissions, in the second SLB from a European gas transmission system operator after Gasunie.

“Today’s transaction is in line with Snam’s commitment towards sustainable finance as a key pillar of its strategy which includes a carbon neutrality target by 2040 and the further development of its energy transition businesses,” said the company. “It will also contribute to the target of achieving more than 80% of its funding through sustainable finance by 2025 compared to 60% as of end 2021.”

Ambition, diversity welcomed

Reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have thus far been the main focus of the SLB market, with around nine out of 10 deals focusing on CO2 emissions.

While investors have generally welcomed this focus, not every issuer has been equally thorough in its approach.

“We recently saw a company that has a good sustainability policy, but they failed to translate that into the sustainability-linked bond,” says van der Meij (pictured) at Actiam. “For example, they have a clear policy on Scope 3, but that wasn’t taken into account in the KPI of the SLB — that’s lacking ambition.”

“We recently saw a company that has a good sustainability policy, but they failed to translate that into the sustainability-linked bond,” says van der Meij (pictured) at Actiam. “For example, they have a clear policy on Scope 3, but that wasn’t taken into account in the KPI of the SLB — that’s lacking ambition.”

The ECB’s focus on climate and environment-related targets has played into their major role in SLB issuance, as well as the requirement that KPIs be material to an issuer’s business.

However, Ligthart notes that some issuers have been more daring, citing the example of a $1bn July 2032 sustainability-linked bond for US mining company Newmont. As well as being the first from the mining industry, the company included alongside Scope 1, 2 and 3 KPIs a target linked to the representation of women in senior leadership roles at Newmont. The latter reflects the company’s involvement in Paradigm for Parity, an initiative aimed at achieving gender parity in corporate leadership by 2030, and the SPT is 50% of Newmont’s leadership positions (senior director level up to and including CEO level) being taken by women by then, versus 25.3% in 2020 and 19.5% in 2018.

Second party opinion provider ISS-ESG found the gender KPI to be relevant, core and material to the issuer’s business model and consistent with its sustainability strategy, but noted that it could have been more material if it had included all manager functions — the metric covers 1.1% of Newmont’s workforce.

Ligthart suggests that an expansion of issuance beyond industrial companies could see a greater range of KPIs being adopted.

“Imagine HR companies or lenders where you could, for instance, have a ‘jobs created’ metric,” he says. “You could have very powerful social impact KPIs, which have so far been a bit underrepresented — they are a bit harder to quantify, but I do hope that this year we will see some spill-over into this area.

“Maybe you could still have, let’s say, CO2 emissions intensity as a headline KPI, but complement that with social impact indicators. That would be a very relevant add-on to the format.”

Eerenberg-van Kesteren at Actiam says the firm would be supportive of an increase in new KPIs such as gender equality.

“Sustainability-linked bonds provide a real opportunity in this respect,” she says, “because a social bond with use-of-proceeds only related to gender, for example, would still be a bit difficult.”

ICMA, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and UN Women in November published a guideline outlining practical ways to use sustainable debt instruments to advance gender equality, which included examples of appropriate KPIs and SPTs.

“We also like to see innovations in this market,” adds Eerenberg-van Kesteren (pictured). “And this is where the human factor comes into play — when we make our quarterly reports, we always pick out one bond to make a little case study out of it, and this is the kind of thing our clients want to see.”

“We also like to see innovations in this market,” adds Eerenberg-van Kesteren (pictured). “And this is where the human factor comes into play — when we make our quarterly reports, we always pick out one bond to make a little case study out of it, and this is the kind of thing our clients want to see.”

Investors nonetheless highlight the need for KPIs and SPTs, whether climate-related or social, to be material and ambitious. AXA IM, for instance, in its framework for assessing SLBs not only cites the SLBP but says that it seeks additionality and favours targets that are new or more ambitious than companies’ existing ones. It suggests that an appropriate KPI for an auto company, for example, could be the percentage of sales related to electric vehicles.

“For any company, GHG emissions are probably material, but it is good to have some industry-specific KPIs,” says AXA IM’s Kotula. “What we want to avoid is issuers choosing a KPI that is not material for its sector.

“One example is ESG ratings as a KPI and an improvement in these as the SPT. Regardless of the sector of the issuer, that’s not material — it’s mainly about disclosure; it doesn’t bring about a meaningful change in the issuer’s ESG profile.”

Hold-ups and step-ups

Financial institutions was the most popular (although perhaps broadest) sector when investors were asked by ABN AMRO which they prefer for ESG bond issuance in 2022, with senior preferred/OpCo FIG issuance also only second behind senior unsecured corporate issuance as the structure investors are most able to purchase.

Berlin Hyp issued the first SLB from a bank in April of last year, a €500m 10 year senior preferred bond with a 25bp step-up in the final coupon should its SPT not be met, but unfortunately for investors and its peers, the European Banking Authority’s position towards the instrument has constrained further supply. The regulator sees step-up coupons or similar compensatory mechanisms as potential incentives to call, preventing their use on loss-absorbing instruments such as senior preferred contributing towards MREL requirements — something that did not apply to Berlin Hyp’s deal but which — under current structures — undermines the viability of SLBs for most banks.

The German bank’s pioneering issue nevertheless set a benchmark for the sector, including an SPT of a 40% reduction in the carbon intensity of assets refinanced in its loan portfolio between 2020 and 2030.

“For banks, Scope 3 emissions are the most relevant,” says Ligthart, “and it was very courageous for Berlin Hyp, as a financial institution, to go out with a Scope 3 SLB.”

Thus far, coupon step-ups have been the most commonly used feature that is triggered by an issuer failing to meet an SPT, but other structures have been floated. In ABN AMRO’s survey, investors were asked what impact they would accept when considering SLBs, and while 64% of investors said they would accept some form of financial compensation — either a coupon step-up (35%) or a premium at maturity (29%) — 9% cited charitable donations, and 11% either a coupon step-down (6%) or discount at maturity (5%) as acceptable.

“When it comes to the more sustainable investors that you would hope to attract, some of them say, well, I’m not that keen on profiting from failure, so to speak,” says Ligthart, “so can’t you maybe work out a charitable donation or a commitment to invest an amount equivalent to the value of the step-up in remediation activities to get the company back on track as soon as possible?”

The use of charitable donations has already crept from the sustainability-linked loan market into private SLBs, and Ligthart says this is “one to watch”.

“That could inspire the market. However, under the SLBP it still needs to be something linked to the instrument,” he adds, “otherwise why not just make it a commitment on a corporate level?

“We’re always trying to innovate and think of new structures, but maybe we risk missing the point — it’s still important to make an offering relevant to investors in the capital markets.”

Step-up coupons themselves are under scrutiny. In spite of the increasingly wide variety of issuers and KPIs/SPTs across the market, the level of coupon step-up typically remains 25bp three years before maturity or 75bp at the time of redemption, something investors find inappropriate.

“What I’m worried about at the moment is that you have many different ambition levels, but still the coupon step-ups are comparable with each other,” says van der Meij at Actiam. “Some targets have to be met quite soon, others are further away. Some are more challenging, some are less challenging. But the coupon step-ups are more or less aligned.

“That aspect of the SLB market is not fair at the moment.”

More SLBs, less haste

As the market heads towards a possible $300bn of outstandings this year, innovation and change is all but inevitable. But whatever the future brings, growth must not come at the expense of quality, says van der Meij.

“At times lately, 50% of the bonds in the market been sustainable bonds, and it’s good that many companies are getting involved,” he says. “But, to be honest, that makes me a little bit nervous that the hurdle is too low.

“Going forward, we will have to ask if our benchmarks are still good enough.”

Eerenberg-van Kesteren says this thinking is likely to be reflected in Actiam’s framework for analysing sustainable bonds.

“Our framework is a year and a half old and we’re now seeing the need to update it to increase the level and make sure that we are at least still buying only the really sustainable bonds and not just those that are simply in line with regulation,” she says.

Ligthart at ABN AMRO says that issuers could also benefit from clarity on best practice for their industries.

“For a couple of sectors, it has been a bit harder to align with the relevant climate scenarios,” he says. “If you look at the Science Based Targets Initiative, they don’t cover all industries — the oil and gas sector guidance, for instance, is still under development.

“It could be helpful for investors’ analyses if such benchmarks were available and aligning with such guidance would also support the credibility of SLBs.”

At AXA IM, Kotula also expects the firm’s approach to sustainability-linked bonds to evolve, noting how young the market remains today.

“It would be a great idea to have the same kind of discussions in maybe a year’s time,” he suggests, “when we will have a lot more analysis available and examples of good and bad practice.

“One very interesting thing to see will be what happens if an SLB issuer fails in meeting its sustainability targets, how the market will react.”

A pdf of this article and accompanying Gasunie case study can also be downloaded here.